bobspirko.ca | Home | Canada Trips | US Trips | Hiking | Snowshoeing | MAP | About

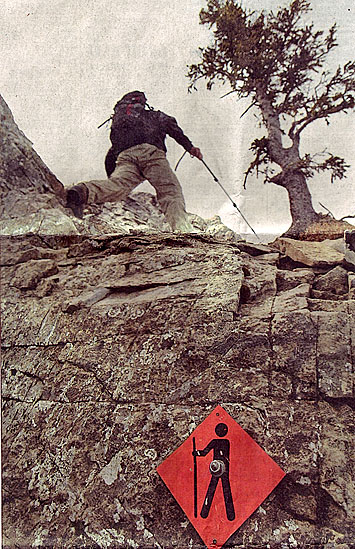

Article from the Calgary Sun

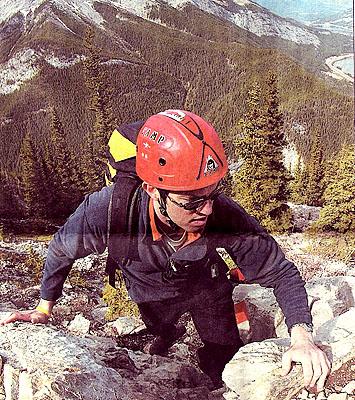

Straddling a ridge beside a 175-metre cliff, David Begg describes the seductiveness of climbing up rock without a rope. "You climb a few rock steps and you just want to keep going and you don't really know where you're going," says Begg, who runs Yamnuska Inc., a climbing school based in Canmore. Begg has just finished his lunch of trail mix and water on the summit of Heart Mountain after two hours of guiding two guests up Heart Creek Trail, located east of Canmore near Lac des Arcs. The trio hiked most of the trail, but had to scramble over a three-metre-high rock step and some steep rocks to reach the summit of 2,135-metre Heart Mountain, the pinnacle of the popular scramble trail Scramble? For most, the word calls to mind eggs or people in a rush. In the outdoors world, it means scrambling up steep rocks using your hands for balance. Unlike its scary big brother, rock climbing, scrambling sounds innocent enough. Scrambling can be pure freedom. It's exciting adventure that allows climbers to move fast with minimal gear on terrain steep enough to give an adrenalin kick. A few steps off route though, and scrambling leaps into the realm of rock climbing. Sadly, some people realize the dangers of scrambling too late. "There are many scramble routes that cross over the line between steep hiking and climbing. If you slip, it might be your last slip," says Brad White, who has been rescuing people stranded on cliff sides for the past 25 years as a Parks Canada mountain safety specialist. One or two people are killed each year scrambling in the Rocky Mountains of Banff National Park. Kananaskis Provincial Park statistics don't differentiate between climbing and scrambling accidents, but at least half of the 47 climbing-related rescues in the park since 2001 have been scrambling mishaps, according to park staff at Alberta Community Development's Canmore office. The other mountainous national parks in the Rockies such as Yoho, Kootenay, Jasper and Waterton see far fewer scramblers, so serious scrambling accidents are rare in these areas. There have been no scrambling deaths in these preserves in the past decade. In Waterton, though, there are more scramblers and more accidents every year, say wardens. On Waterton's Crandell Mountain alone, 30 people have been rescued in eight accidents since 1995. Brent Kozachenko, a Waterton National Park warden who spent 20 years as a mountain safety specialist, says there have been many close calls. "I've had people stranded on cliffs who couldn't move," Kozachenko says. Why no deaths? "Divine providence," Kozachenko says with a chuckle. The typical scrambling accident victim is a male between age 17 and 25 who has lived in Banff less than two months. Eager to reach the peaks all around their new home, these young men hear they can bag most of them without rock climbing, say climbing guides scrambling and wardens. The inexperienced hikers quickly latch onto the notion that scrambling doesn't require special training or expensive climbing gear, another factor for these men, many of whom work at low-paying jobs in the tourism service industry rock climbing. Wardens and guides in most of the mountainous parks of southern Alberta warn that inexperienced hikers risk their lives by heading off to learn on their own armed with only a scrambling guidebook. Few scramblers have taken a proper training course, and many beginners don't bother to find an experienced partner for their first trips. |

"On of the problems we face is how many people are moving out to Calgary each year with no background in the mountains, but who want to be enjoying the mountains," says Burke Duncan, with Alberta's Community Development office in Canmore. "You've got a guy who's 19 working at a Banff hotel and he just goes for it. You've got no fears when you're young," Begg says, whose company will offer its first scrambling courses for the public this spring and summer. "We always advocate taking a course, because you can learn so much from experienced climbers." Those statistics aren't kept for the number of climbing trips versus scrambling trips in the mountain parks each year, some outdoor experts consider scrambling more dangerous than climbing. "Scramblers, in general, seem to be a group that is a little less aware of the dangers involved. Climbers more often have more training and experience before they go out on their own," Kozachenko says. Climbers who use proper gear and techniques are usually caught by their rope when they fall. Most climbers take courses run by professionals before heading out with a partner. Scramblin doesn't have the same built-in fear factor. Every year, climbing wardens throughout the Rockies rescue dozens of scramblers who start up mountains alone, only to get lost on the way up or stuck in a terrain trap on the way down. "It always looks easier from the bottom than it is," White says. The majority of accidents are on the descent. Testosterone and ego often stop scramblers from turning around before they're in over their heads. It's usually easier to commit to going up than down. "Human nature's such that you try to push yourself a little further before turning around," says White, who recommends scramblers stop and call for help if they find themselves in over their heads. Begg's airy perch is 500 metres above the Heart Creek trailhead. Just a few hours before, he stood in the parking lot east of Canmore looking up at his route. Now, he stands a short walk from the summit, taking in the stunning panorama of the front ranges of the Rockies. Just out of Begg's view to the west is the base of the 175-metre cliff below the summit, where a rescue party found the body of a 27-year-old Calgary woman in July 1995, after a two-day search. On her first solo scramble, she fell to her death. "What's seductive is the climbing," Begg says after a moment of reflection. "You quickly get into trouble." |

Smart Scrambling Taking a course could save your skin. Yamnuska Inc. is set to

offer its first scrambling skills course open to the public. |

Tips for safe scrambling |

Every

summer, Duncan rescues scramblers and climbers stranded on peaks in Kananaskis

Every

summer, Duncan rescues scramblers and climbers stranded on peaks in Kananaskis